Events

International Conference ‘The Intellectual Heritage of the Jews of Vilnius’

17 10 2023

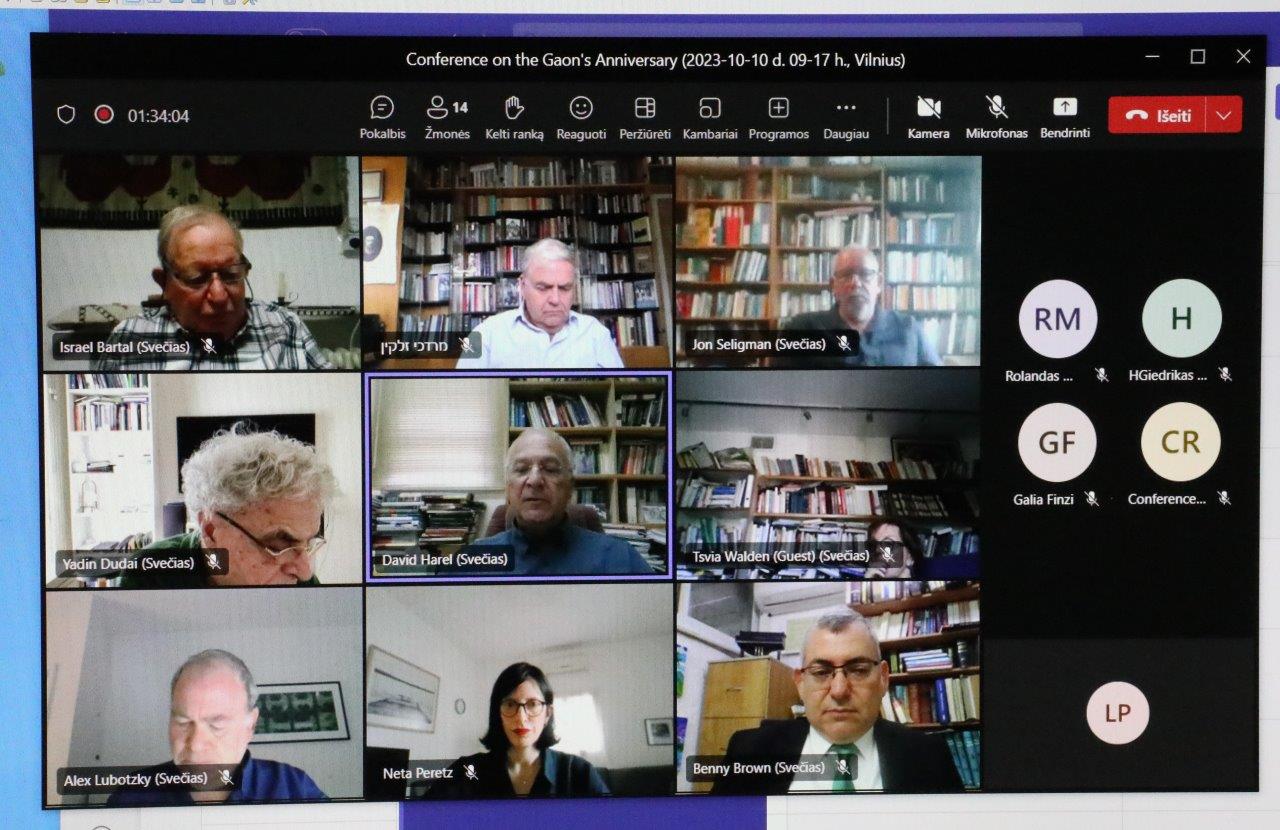

On 10-11 October 2023, this international conference, organised by the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences and the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, was held in Vilnius. Unfortunately, due to the tragic events in Israel on the eve of the conference, most of the speakers from this country were not able to come to Vilnius and participated in the event remotely.

In Lithuania, the year 2020 was the Year of Lithuanian Jewish History and of the Vilna Gaon, to mark the 300th anniversary of his birth. A conference organised by the academies of sciences of both countries was part of the commemorative programme, but since it could not happen that year due to the pandemic, it was postponed to 2023. Also, a decision was made to broaden the scope of the conference by exploring the intellectual heritage of the Jews of Vilnius from the eighteenth century onwards. On the first day of the event, the speakers addressed the intellectual heritage of the Jews of Vilnius in the eighteenth-nineteenth centuries, and the second day was devoted to the process of intellectual modernisation of the Jews of Vilnius and their spread in the world.

Jūras Banys, President of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, opened the conference and asked for a minute of silence in memory of the victims of Hamas’s atrocious attack on Israel. He said he believed that terrorism would lose and we would live in peace again. The peoples of both countries know what the fight for freedom is. That is why Lithuanians are so active in supporting Ukraine in its fight against the axis of evil formed by the Russian Federation, Iran, and, as we see, the terrorists of Hamas. We cannot forget history, especially the Holocaust, which left a deep imprint in the history of Lithuania. It was a tragedy of indescribable scale for the Jewish people. We must remember history and learn its lessons, and that is why the Jewish community of Vilnius is always in our minds.

He stressed that even at such a complicated time, a conference like this can evolve into an excellent beginning of inter-academy cooperation. It is the first joint event organised with the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, but by no means the last. At the end of his welcome address, Prof. Banys thanked everyone who contributed to the organisation of the conference.

Hadas Wittenberg Silverstein, H.E. Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the State of Israel to the Republic of Lithuania, said she was convinced that the hostages seized by the terrorists would be returned to Israel. Many people worked hard for this conference to take place. It is sending the message that we must be resilient and fight for life because the spirit of Jerusalem is burning in the hearts of each of us.

Prof. David Harel, President of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, who spoke next, also gave a brief description of the situation in Israel; he said it was quite terrible at the moment. The people, including the professor’s two grandsons who are in the Israel Defence Forces, are fighting a dangerous enemy. In his opinion, things will be different in the country in the wake of these events. Even now, the proportion of killed Jews in the overall population is several times greater when compared to the proportion of Americans killed in the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 in the USA.

Prof. Harel added, that in Vilnius, the Strashun Library and the Jewish press were important components of culture. The Vilnius Gaon was famous as a Talmudic scholar. Thanks to him and other intellectuals, Vilnius became an intellectual centre. The Nazis ruined everything. The Vilnius Gaon was well known for his diligence. He slept very little. He argued that wisdom was a remedy for the soul, and the soul was a remedy for the body. Learning is a fundamental necessity of existence. The Vilnius Gaon firmly believed in the potential of education to change people, to enrich their existence, and impart meaning to it. Broad knowledge had to liberate people from obscurantism and superstition. From Vilnius, these ideas spread across the world. For this reason, even now academic collaboration is very important, it emanates from Vilnius Gaon’s scholarship. To create a democratic society and preserve it, we must observe changes and be vigilant.

After the introductory part, a movement Nigun from Ernest Bloch's Baar Shem was played by a violinist Rashel Avital Katz from the Jerusalem Music and Dance Academy, accompanied by Ina Vyšniauskaitė from the National Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis School of Arts in Vilnius.

The welcome addresses were followed by the presentations. In his opening lecture, Prof. Benjamin Brown from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem talked about the theological-political legacy of the Vilnius Gaon. Rabbi Elijah ben Shlomo Zalman, the Vilna Gaon (1720–1797), was not a systematic thinker, certainly not in political philosophy. He never developed a political theology. However, in several places throughout his writings, he addresses some of this discipline’s fundamental questions in ways that may echo modern concepts. The Vilna Gaon advocates a government based on public consent. Like Charles de Montesquieu, who distinguished between regimes founded on ‘love of the laws and of our country’, on moderation, on honour, or on fear, the Vilna Gaon delineates regimes founded on honour, on fear, or on peace. He spoke of the need for distinct branches of government, enumerating four: legislative, executive, judicial, and enforcement, and maintained that these branches should be administered by Torah scholars. He occasionally hinted at a utopian, semi-anarchistic ideal in which God rules over all humanity and no human governed another. In nineteenth-century Lithuanian Jewry, where the Vilna Gaon was a towering figure, a number of thinkers adopted similar political ideas and developed them in different directions.

Prof. Yadin Dudai, of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, chaired the first session on the intellectual heritage of the Jews of Vilnius in the eighteenth-nineteenth centuries. He admitted that to him, Vilnius had a huge influence due to an enormous loss. His relatives were murdered in Paneriai. This loss distressed the family. In those days, Vilnius was an important centre of Jewish culture. For instance, two of his relatives were journalists in Vilnius. There were numerous cultural and educational institutions in the city.

Prof. Israel Bartal, of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, gave a lecture ‘“Each Generation and its Scholars”: The Changing Faces of the 'Historian's Gaon’. There is no doubt that in the eighteenth century, the scholarly creation and intellectual leadership of Rabbi Elijah ben Solomon Zalman (1720-1797, known as the ‘Prodigy of Vilnius’) played a major role in shaping the historical writing on Eastern European Jewish society. Several generations of writers, from early maskilim and conservative Talmudic scholars, up to radical socialists and modern religious Zionists, presented the man and his teaching in a variety of historical narratives, from quasi-hagiographic depictions of the exemplar pre-modern rabbinic authority on the one hand, to a forerunner of Jewish Enlightenment on the other hand. This speaker offered a review, updated in 2023, of two centuries of changing historical narratives in their different contexts and called for a closer look at the Gaon in his real time and place. One can argue that he was one of the creators of modern Judaism. The Vilna Gaon was a pioneer or a source of new ideological and intellectual trends, a herald of religious Zionism.

This theme was taken further by Prof. Alex Lubotzky from Weizmann Institute of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. In his lecture ‘The Mathematics of the Vilna Gaon’, he acquainted the audience with a mathematical book by the Vilna Gaon, which was based on his notes and published posthumously. The title of the book is איל משולש (Ayil Meshulash; Triangle), and it gives some insights into the Vilna Gaon’s knowledge of algebra, trigonometry, geometry, and some aspects of astronomy.

Academician V. A. Bumelis chaired the second session of the first day of the conference; he introduced speakers from Vilnius University and the University of Wroclaw. He said he was expecting interesting presentations and a discussion about the intellectual ecosystem in Vilnius of those times.

Prof. Jurgita Verbickienė of the Faculty of History of Vilnius University and the head of the Centre for Studies of the History and Culture of East European Jews, also at Vilnius University, gave a lecture ‘The Space of Intellectual Life: Jewish Socio-Topography of Vilnius in the Second Half of the Eighteenth Century’. The Vilna Gaon was an outstanding figure in the Jewish milieu of Vilnius. When assessing his merits, it is often emphasised that he lived and thought in an environment that created conditions for it and appreciated his genius, but questions are rarely asked as to how exactly he lived and what that environment was like. The presentation is dedicated to the socio-cultural and socio-topographical analysis of the residents of the Jewish quarter of Vilnius and Vilna Gaon‘s neighbours during his Vilnius period. The key source of the research presented is the 1765 and 1784 Jewish censuses of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Marcin Wodziński, a member of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Academia Europaea, works at the University of Wrocław, Poland, where he runs the Taube Department of Jewish Studies and holds the position of professor of Jewish history and literature. The theme of his presentation was ‘Two Enlightenments: The Case of Josef Rosensohn of Vilna’. Joseph Rosensohn (c. 1774–1849) was a Vilna-based rabbi, a medical doctor, and a maskil (follower of the Jewish Enlightenment). He was also the author of the oldest maskilic treatise on Hasidism written in either late 1804 or 1805, so far unknown to the scholars. In his lecture, Prof. Wodziński demonstrated why this treatise was a critically important source for the history of Haskalah and Hasidism, and especially for the history of the Lithuanian Jewish orthodoxy, Jewish-Christian relations, and more. It provides some unknown or corrective information and sheds entirely new light on the emergence of the misnagdic circle in Vilna, the relations between the Vilna Gaon and the Jewish community, and the early anti-Hasidic conflicts in Lithuania.

After this lecture, the conference moved to the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History. There, Dr Jon Seligman, a senior research archaeologist at the Israel Antiquities Authority, gave a talk on the excavations on the site of the Great Synagogue of Vilnius. Although only a small fraction of the historic synagogues and other Jewish communal buildings of Lithuania survived the Holocaust, they are an essential and integral part of the cultural heritage of Lithuania. None was more consequential than the magnificent Great Synagogue of Vilna, the oldest and most significant monument of Litvak Jewry. As the Jews of Vilnius constituted such a significant proportion of the city’s population, this monument should be viewed culturally as one of the Vilnius’ cathedrals. The baroque synagogue, built on remains of an earlier wooden synagogue, was constructed in the seventeenth century and became the heart of one of Europe’s most important Jewish communities. Located at the centre of a communal courtyard (Shulhoyf), together with eleven smaller synagogues, a bathhouse, kosher butcheries, a library and community offices, the Great Synagogue would go through a series of changes until its tragic ransacking and demolition under the Nazi and Soviet regimes.

After Dr Seligman’s lecture, the participants visited the exhibitions at the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History and watched the film Daughter of Vilna: The Life in Song of Masha Roskies about the fate of Masha Roskies, the mother of Prof. David G. Roskies, a speaker at the conference, Sol and Evelyn Henkind Chair emeritus in Yiddish Literature and Culture and professor emeritus of Jewish literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. The professor admitted that personally to him, the screening of the film was ‘not only an overwhelming emotional experience. It was also the first time that I “saw” it through the eyes of a Lithuanian audience, who never experienced Jewish Vilna first hand’.

The second day of the conference opened with the lecture ‘The Yiddish Avant-garde Group Yung Vilne and Vilnius University: Separate or Interconnected Worlds?’ by Prof. Mindaugas Kvietkauskas, the dean of the Philology Faculty of Vilnius University. He spoke about the venues of the main Polish cultural and literary activities in interwar Vilnius. In the 1930s, the elderly cultural generation of the early Polish Modernism (Ferdynand Ruszczyc, Marian Zdziechowski, Witold Hulewicz, and others) were challenged by the left-wing avant-garde and the bohemian youth of Vilnius University, which formed the famous literary group Żagary (1930–1940). The formation and activities of Yung Vilne (1929–1940), the most prominent Yiddish literary and artistic avant-garde group in interwar Vilnius, paralleled these processes, and there were many similarities in the work of the authors of both circles who belonged to the same generation (social criticism, avant-garde expression, the significance of the Vilnius identity, catastrophism). However, only fragmentary facts about contacts between the Yiddish and Polish avant-garde milieus are known. The memoirs and research highlight the isolation that existed between the Polish and Jewish literary worlds in Vilnius. This distancing was particularly due to the rise of anti-Semitism at Vilnius University in the 1930s. The aim of this paper was to reconsider the thesis of the mutual isolation between Yung Vilne and the Polish literary and intellectual life centred around Vilnius University.

Next to speak was Saulė Valiūnaitė, a doctoral student at the Faculty of History of Vilnius University, who is currently working on her thesis ‘Yidishistkes Preserving Yidishkayt. Women's Input into Forming and Preserving the Secular Jewish Identity in Interwar Vilnius’. The title of her lecture was ‘Unknown Soldiers? Women in the Politics of Doikayt in Interwar Vilnius’. It turns out that in interwar Vilnius, women already had opportunities to participate in communal and political activities and were involved in the activities of the Bund and the Folkist political parties, which supported the concept of doikayt (Yid. ‘hereness’). However, in analysing the case of interwar Vilnius, women's input to the dissemination of the diasporist ideas remains comprehensively unresearched. The speaker’s aim was reconstructing women’s activities in the Bund and the Folkist party and to analyse women’s contribution to the dissemination of the ideas of doikayt.

Dr Lara Lempertienė, head of the Judaica Research Centre at the Documentary Heritage Department in the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania and the curator of its Judaica collection, delivered the paper ‘On Vilna with Love. Zalman Shneur and Hermann Struk’. In 1923, the poem Vilne (Vilnius) by famous poet Zalman Shneur was published in Berlin as a book illustrated with the etchings by no less celebrated artist, Hermann Struck. Dr Lempertienė spoke about the history of that publishing project, which was inspired by both authors’ love for Vilnius.

The lecture of Prof. Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, an art historian and exhibition curator, a leading researcher at the Lithuanian Institute for Culture Research, and a professor at Vilnius Academy of Arts, was about ‘Art of Jewish Women Artists in Interwar Vilna’ (the presentation was delivered by Dr Laima Laučkaitė-Surgailienė, Prof. Jankevičiūtė’s colleague from the Lithuanian Institute for Culture Research). This topic has not been systematically studied so far, although the current state of research already allows us to talk about the work of Jewish women artists as a distinct phenomenon, which deserves separate attention and adds to our understanding of Jewish culture and social life in Vilnius and of the state of the city's art field in general.

Women's names appear in the sources of Jewish artistic life of Vilnius already in the early 1920s, and they become more numerous in the 1930s. This phenomenon is linked to modernisation and the growing trend towards emancipation, which affected the lifestyle of the Jewish community of Vilnius and the position of women in society in general.

Prof. David G. Roskies, Sol and Evelyn Henkind Chair emeritus in Yiddish Literature and Culture and professor emeritus of Jewish literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, gave his keynote lecture ‘A Tale of Two Cities: Growing Up in Vilne de-Kanáde’. This lecture reflected his personal perspective on how klal-tuers (communal leaders), pedagogues, and poets transplanted the languages, spirit, and substance of Jewish Vilna to Montreal, the economic and multicultural hub of French Canada, after the Holocaust.

In her lecture ‘From Kalman Schulman in Vilnius to Hebrew speaking children in Israel: Laying the Foundations of Modern Hebrew Culture’, Tsvia Walden, professor emerita of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, spoke of her research dedicated to a second life of a language, when after 2000 years it renewed itself as a mother tongue. The last testimony of Hebrew being spoken at home is dated to the second century. Linguists are divided as to whether we should talk about the revival, the renewal, or even the emergence of contemporary modern Hebrew. Some argue it was a dead language, others prove it has never stopped living, though its path was unusual. Yet there is a general agreement that, against all odds, it has evolved into a second life as a mother tongue. Kalman Schulman, a Jewish writer who pioneered modern Hebrew literature, was born in Vilnius in 1819 passed away in 1899, just a year after the first Hebrew speaking kindergarten was founded in Rishon LeZion in Palestine. In her talk, Prof. Walden discussed the contribution of Kalman Schulman's translation of Eugène Sue's novel Les mystères de Paris (The Mysteries of Paris), very popular among young adult readers, to the renewal of modern Hebrew as a mother tongue.

In the closing lecture of the conference, Prof. Mordechai (Motti) Zalkin, of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, spoke about the intellectual heritage of the Jews of Lithuania. He pointed out that the prevailing perception of the intellectual heritage of Lithuanian Jewry, both in the popular discourse and in the academic debate, begins, and many times even ends, with the question of the scholarly/cultural heritage of the Vilna Gaon. However, most of the supporters of this approach focus exclusively on the ‘bequeather’, that is, the Vilna Gaon and his scholarly world, but completely ignore the question of whether this can indeed be seen as a legacy: whether, and to what extent, his intellectual and religious views were accepted in the Ashkenazi Jewish society in general, and in the Lithuanian Jewish society in particular. In this context, it is necessary to mention another assumption, which was not proven in the research, which considers the Lithuanian Yeshivas as a central element in the Gaon's legacy. The focus on this approach prevented, to a large extent, the possibility of examining other and important aspects of the intellectual heritage of Lithuanian Jewry, such that their influence is still evident today. For example, the educational system of the Jewish Enlightenment in Eastern Europe, of which Vilna was one of the first and most important centres (and which, unfortunately, is not discussed at all in this conference) not only elementary and secondary schools, but also the extensive and extraordinary participation of thousands of Jewish young men and women in the higher education system. In his lecture, the speaker proposed a new model for examining the question of the intellectual heritage of Lithuanian Jewry in general, and of Vilnius Jewry in particular.

After the academic part of the conference, the speakers and the participants took part in a guided tour of the Jewish Vilnius. The guide Julijanas Gurvičius showed around and spoke about the places in the Old Town of Vilnius where the Jews studied, created, and prayed, and reminisced about the most famous cultural figures in Vilnius, illustrating his stories with anecdotes and illustrations pulled out of his backpack as well as various incidents from the lives of doctors, benefactors, the wealthy and the beggarly, musicians and artists. By the way, Prof. David G. Roskies took the role of the guide and spoke about the poor Yiddish author Ayzik Meyer Dik, who was an influence on later Jewish literary fiction. The professor is probably the only person to have read all 250 of the writer’s works and written a thesis on him. And when the time came to part and say goodbye until the next similar events, Prof. Roskies expressed his gratitude to the Lithuanian organisers of the conference with these kind words: ‘Thank you, you have done God's work’.

Prepared by Dr Rolandas Maskoliūnas, chief specialist for public relations, and Dr Andrius Bernotas, head of the Organising Department

Translated by Diana Barnard

Photography by Virginija Valuckienė

Conference video recordings: 2023-10-10, 2023-10-11